Time is a surprisingly elusive concept that underpins every aspect of reality — experientially, scientifically, philosophically, the nature of God, and of course the re-presentation of the Passion in the Mass.

When the universe burst into existence at the Big Bang, all of the matter and energy contained within it also came into existence. Where there is no matter present, there is no time.1 One of the greatest accomplishments of Einstein’s Theories of Special and General Relativity was to demonstrate that time is a fundamental property of matter, similar to gravity, mass, charge and so on. Without matter, there is no time.

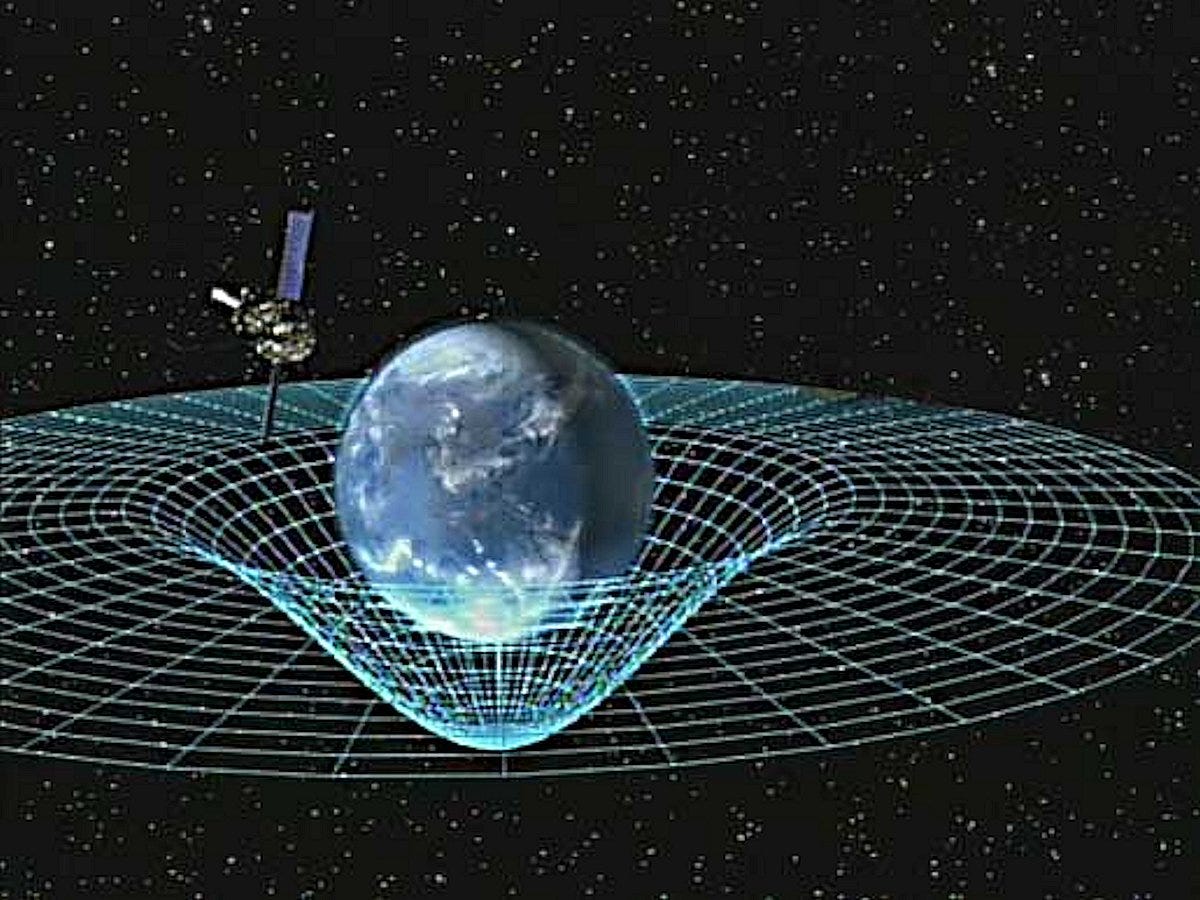

Time is not constant. It changes depending upon gravity and the relative speed at which an object moves. The faster something moves, the slower time goes. Therefore, time is different for every object in the universe, however for objects moving at the “same speed” and in close proximity, the time differences are too slight to be noticeable. Strictly speaking, there’s no such thing as things existing or truly being at “the same time.”

Let’s take as a real world example the satellite GPS that is now included on every smartphone. The satellites orbiting the earth that are used to triangulate locations here on earth by our phones and other navigation devices are thousands of miles in the air and moving at thousands of miles per hour in order to stay in their proper “fixed” orbits. Because of their relative speed and location, time as measured at the satellites is different from time for objects here on earth. If engineers did not correct for time differences, GPS readings on the surface of the earth would be off by an average of seven miles. The relativity of time is very, very real and a practical problem in the modern world.2

The equations used in Einstein’s Theory of Relativity require that at the moment of the Big Bang, the numerical value used for time must have equaled zero. Therefore, God, as an eternal, spiritual and immaterial being, who pre-exists the universe and is outside of the universe must also be outside of time. God must therefore be “timeless.” But what does that really mean?

We know from Scripture, apparitions, locutions, etc., that God has the ability to foretell the future. Can he do this because he is infinitely intelligent and can correctly calculate all the variables and logical possibilities? As long as free will exists in Creation to even the smallest degree, predicting the future would be impossible even for an infinite intellect such as God. By definition, what a free person will choose to do or not do cannot be reliably anticipated. The slightest unpredictability in any system will cause dramatically different future potential outcomes. As St. Thomas Aquinas quotes Aristotle, “a slight initial error eventually grows to vast proportions.”3

So if the future cannot be calculated because of the unpredictability of free will, then the only alternative explanation for God’s amazingly accurate prophetic powers must be that he observes the future — and by extension, the present, and the past simultaneously. When he reveals a prophecy, he is simply reporting what he already knows. He knows it because he exists in a perfect existential moment where everything that is real is fully present to him at all “times.” By definition, because God is “I Am Who Am,” or in other words, “I Am What Is,” all reality exists within and is him. The Father exists in a perfect existential moment — where all that is and knows is always and fully present to him. This eternally generated self-Image of the Father is his eternal and uncreated Son. The infinite communication of this divine Image between the Father and the Son is the Holy Spirit.

God is inescapable. The future is already known and fully exists to God. It is just not known to us who are trapped in the transient present of this life. If God is the definition of Reality and what he knows is real, then a lot of interesting paradoxes arise, not just for him, but for us. Does that mean that we are fallen and redeemed at the same time? Are we in heaven (or hell) and on earth simultaneously? Are we like Schrödinger’s cat4 both alive and dead until we are observed? The answer to these and other paradoxes lies in the way we experience reality, and in particular time, differently from God and from the way we will (and do?) when we will be (and are?) glorified ourselves.

There are three types of time. Of course, the most familiar type of time is linear or sequential time—the time that we experience in our current mortal reality. There are also two other types of time, the eternal and the everlasting. Both linear time and eternal time are created. The everlasting, which may not even truly be considered time at all, is uncreated and therefore only belongs to God. Many of the Fathers addressed the notion of time, but perhaps the best known is St. Augustine.

Addressing himself to God in “Confessions,” he says,

It is therefore true to say that when you had not made anything, there was no time, because time itself was of your making. And no time is co-eternal with you, because you never change; whereas, if time never changed, it would not be time. What, then, is time? There can be no quick and easy answer, for it is no simple matter even to understand what it is, let alone find words to explain it. Yet, in our conversation, no word is more familiarly used or more easily recognized than “time.” We certainly understand what is meant by the word both when we use it ourselves and when we hear it used by others. What, then, is time? I know well enough what it is, provided that no one asks me; but if I am asked what it is and try to explain, I am baffled. All the same I can confidently say that I know that if nothing passed, there would be no past time; if nothing were going to happen, there would be no future time, if nothing were, there would be no present time.5

One can get a sense of Augustine’s dilemma by thinking about something as seemingly obvious as the “present.” Once you try to think of and focus upon the present moment, it has already passed. So can one really say that there is any such thing as the “present” if it cannot be defined or captured, if it is gone before it can even be grasped or perceived? Because of this dilemma, Aristotle and others make the disconcerting argument that time may not exist at all. The present is elusive, the future is not here (so it can’t really be said to have any existence), and of course the past is irretrievably gone. So what is time if none of its components are “real” in any meaningful sense?

Whatever time is, we at least have an intuition that we exist in linear time because there is movement and change around and within us.6 Eternity is at least linear time (whatever that is) without end, but that may not be quite true either. A better Christian understanding of eternity is not that it is endless linear time, but rather that it is time stopped. Everything that is known and knowable is known and experienced in one existential moment, an eternal present—all at once. That is the way God experiences. Everything that he knows is present to him at all times. However, the everlasting is different from the eternal and is a unique characteristic of God. St. Basil the Great calls the everlasting that which is “older than all time and eternity in its being.”7 The everlasting is uncreated and can only belong to the uncreated God. Therefore, the everlasting easily surpasses even the eternal, which is created by the everlasting God. As something unique and uncreated, it is also therefore not fully knowable to us who are created even if we achieve deification and experience eternal time — in other words — the past, present and future all at once. In both everlasting and eternal time, things exist as perfect existential moments.

Time for God is like a complete book. His mind can perceive the book in its entirety. In our current time-bound state, we cannot. We can only grasp one page at a time, beginning with the first and progressing to the last. Linear time is what happens when the existential moment (the complete book) is fragmented into little pieces (individual pages). We experience our lives as the flipping of one page at a time; whereas in the mind of God, the entire book exists as a complete whole. Another image is to think of reality and time as a flowing river within which we are submerged. We observe it as it relentlessly moves and passes around us. We are truly adrift in a river of time. So, for us, since there really isn’t any stable present, can we say that time isn’t “real” in any commonly understood sense (we know that time is elastic in physics, etc.)?

Instead of speaking of the current “time,” should we instead talk about the “actual” for us, whatever that is, particularly since we exist in and experience time individually?

The difference between time for us and God is really a question of perspective. He sees and encompasses the river in its entirety. We are in it and can only see what is near us and flowing along with us. Another way to think of the “actual” for each of us in our present life is to see our reality as a moving picture window. We can see reality only through the limited perspective of the window as it moves through time. What is outside the limited perspective of the window is not definitively known and can only be inferred. When we are united to God in eternity, our eternal time will resemble God’s everlasting time in many ways. Our experience will be what has been described by the Church Fathers as “still perpetual motion,” God’s characteristic that St. Thomas describes as “perfect act and perfect potency.” We will share what God is and what he experiences, but without his uncreated essence. We will share God’s perspective, which is everything. There are no more rivers or moving picture windows.

t=0 at the instant of the Big Bang.

Richard W. Pogge, “Real World Relativity: The GPS Navigation System,” accessed March 26, 2025, https://www.astronomy.ohio-state.edu/pogge.1/Ast162/Unit5/gps.html.

St. Thomas Aquinas, On Being and Essence, trans. Armand Maurer (Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies, 1968), 28.

“Schrödinger's cat,” Wikipedia, accessed April 1, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schr%C3%B6dinger%27s_cat.

St. Augustine, Confessions, trans. R.S. Pine-Coffin (New York: Penguin, 1961), 264.

That is why “time” can be thought of as a measurement of change.

Georgios Mantzaridis, Time and Man, trans. Julian Vulliamy (South Canaan, PA: St. Tikhon’s Seminary Press, 1996), 7.